6 minutes

Abusing VS Code’s Bootstrapping Functionality To Quietly Load Malicious Extensions

Wow, been a while since my last blog 😅. During some research I came across a technique variation which I felt was interesting enough to share in a brief blog post. It relates to how the bootstrapping functionality in VS Code can be abused to quietly load plugins - it may come in handy during your initial access adventures!

The Threat of VS Code Extensions

It’s no secret that the popularity of VS Code brings a lot of risk exposure in the form of its plugin system. Threat actors and researchers alike have been happily abusing it to target developers - even your favorite dark theme is not safe.

Of course, this type of threat is inherent to allowing untrusted (or semi-trusted?) code to run within a trusted process. As attackers, it’s very enticing to be able to run our own code inside of the trusted, signed, and highly prevalent process “Code.exe”. This process is also known to perform a variety of activities, like call out to the Internet, spawn shells as child processes, and continually interact with local and remote filesystems. This makes it hard for defenders to fingerprint what constitutes benign versus malicious behavior, and by extension makes it easier for us as attackers to “blend in” with the noise.

Creating malicious Code extensions is outside of the scope of this post. However, creating custom VS Code extensions is easy, the team even has a great getting started guide for it. You’ll manage. 😉

VS Code Extensions for Initial Access

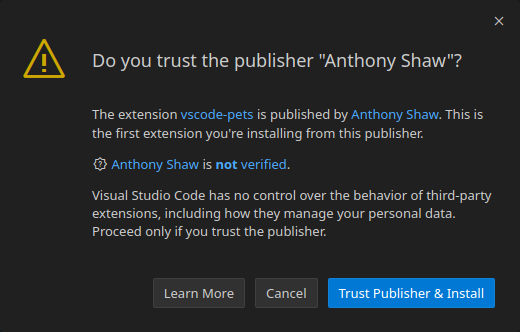

(Un)fortunately, getting a malicious plugin installed is not as arbitrary as it may seem. Clearly, the VS Code team is aware of this threat, and a number of measures are taken to reduce the risk of a malicious extension inadvertently being installed. There are however several ways of increasing the likelihood of a successful installation: the team over at MDSec has an excellent blog post highlighting various delivery techniques including the VS Code URL handler that still work today. Even so, getting a user to install your plugin triggers various prompts that require some clever social engineering to navigate. In the recent January release, the VS Code team added yet another prompt that needs to be accepted for every plugin publisher:

VS Code’s “Bootstrap” Feature

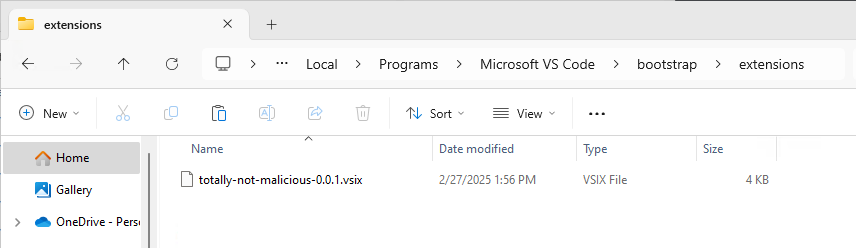

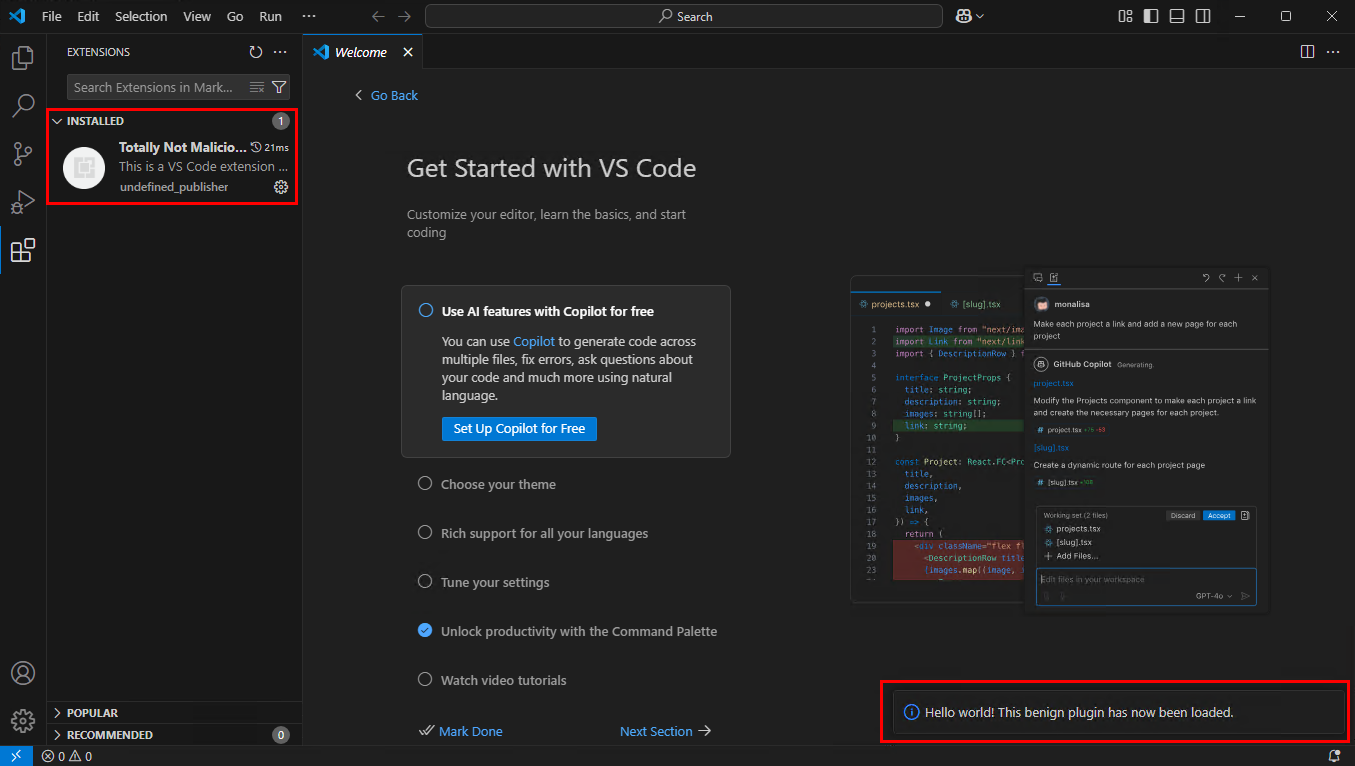

However, there is a trick to get around these prompts and quietly install your plugin. This trick comes in the form of VS Code’s bootstrapping functionality, which enables enterprise users to install new instances of VS Code with pre-packaged extensions. As the documentation describes, bootstrapping a new install of VS Code is as simple as creating a ./bootstrap/extensions folder within your VS Code installation directory and dropping the .vsix (extension) files in there. This installs the extension(s) on first boot, bypassing any prompts (including the new publisher trust prompt). This has the added benefit of not requiring the extension to originate from the marketplace, which is obviously a great thing when deploying malicious extensions as it bypasses the need for publisher or security checks.

However, there is an issue with this method. While it works well for a “Bring-Your-Own” installation of VS Code, it does not work on systems where VS Code is already installed. This is because the ExtensionsInitializer (source) stores a value in the StorageTarget.Machine field, which is machine-specific (on Windows it equates to %AppData%\Code). This field ensures the ExtensionsInitializer only runs on first boot, meaning we are out of luck if the key is set on subsequent runs. Or are we?

Note: Removing the

%AppData%\Codedirectory does “reset” the settings inStorageTarget.Machine, and makes it so the bootstrap functionality works even for users who have extensions configured in their user profile (which is typically in%USERPROFILE%\.vscode), merging the bootstrapped extensions with their own. However, this directory contains other important configuration data such as thesettings.jsonfile, so taking this approach is not recommended. If you want to persist within a user’s existing profile, backdooring the user’sextensions.jsonis probably the better route.

Making It Portable

To bootstrap extensions on a machine where VS Code is already installed and initialized, we can (ab)use VS Code’s “portable” functionality. As described on this page, a VS Code installation becomes portable simply when a ./data directory exists within it. If this is the case, it will use this directory to store both user AND machine preferences. This means that if this directory is empty, VS Code will assume it is a new installation and trigger the bootstrapping process!

This unlocks a variety of attack scenarios that could be interesting for initial access or persistence. An attacker could use the legitimate VS Code installation zip (or bring their own), and simply inject the ./data and ./bootstrap/extensions directories to silently install and run the malicious extension. Alternatively, bootstrapping could be abused to inject an extension in the user’s existing VS Code installation (see caveat below), then use the extension to restore the user’s normal environment. All without any prompts or warnings!

Note: In my testing it was not possible to simply create a

./datadirectory in the default VS Code installation folder to convert it to a portable install. Analyzing the portability source code (source), this appears to be because the following value evaluates toFalse:const isPortable = !('target' in product) && fs.existsSync(portableDataPath);Analyzing the flow of the logic, we can see that the

productobject is instantiated from theproduct.jsonfile (source), which exists in the./resources/appfolder in the installation folder. For installations that were done using the installer, this file will have a value like like"target": "user", which effectively ignores our bootstrapping.We can confirm that this is the case by removing the

"target"line inproduct.json, and attempting to bootstrap the installation directory again. Now the bootstrapping works, and we can bootstrap into an existing VS code installation!

Prevention and Detection

VS Code outlines how you can use Windows Group Policy to configure various settings, including allowed extensions. Doing so allows you to specify certain publishers, extensions, or even extension versions that will be allowed in your organization. This does require some setup and maintenance, but it is probably the best line of defense against all sorts of plugin-based attacks. Unfortunately there are no filters for extension prevalence or verified publishers, but the VS Code team states they are open to suggestions if that’s a need for your organization.

Now, I’m no expert in terms of detection, but it seems to me like the behavior of VS Code is pretty hard to fingerprint due to the broad spectrum of use cases it has. As such, detecting uncommon child processes of Code.exe for example may be quite challenging - it’s very common for Code to be spawning shells after all. Avenues of detection may be the following:

- Creation of a

./bootstrap/extensionsfolder inside an existing VS Code installation directory - Creation of a

./datafolder inside an existing VS Code installation directory - Execution of

Code.exefrom a non-default installation directory - Creation of any

*.vsixfiles from a non-Code process

(Suggestions welcome! Feel free to share any ideas and I’ll add them to this blog post)

VS Code Offensive Security Initial Access Red Team

1183 Words

27-02-2025 (Last updated: 28-02-2025)

4c1e6b3 @ 28-02-2025